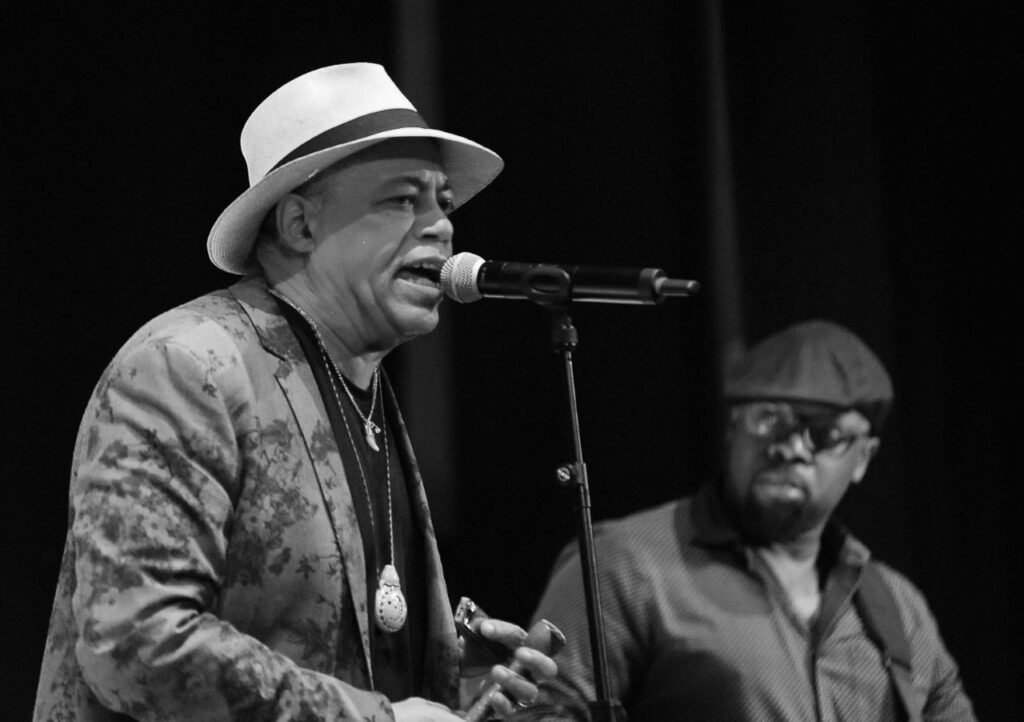

The Harmonica Man

by Matteo Bossi

We reached Billy Branch a few days after the second memorial for Marino Grandi, held at Black Inside in Lonate Ceppino and so, given their longstanding friendship, it goes without thinking that the first words of our conversation are about him. “Marino was such a good guy and I know mama Luciana and Davide are still feeling the loss, And I always looked forward when I would come to Italy to see him and mama. Typically they would present with a bottle of grappa!”

We remind him of their last meeting at the 2019 Milano Blues Session, a few months before the release of “Roots And Branches – The Songs of Little Walter” (Alligator), his previous record. Now he’s got another album, aptly titled Blues Is My Biography, which is the debut for a new label, Rosa’s Lounge Records, from the eponymous Chicago blues club.

Why did it take you six years to do another record?

Well, I wanted it to be good! I feel satisfied by my recording output because I’ve never put out anything that I didn’t like. I think everything that I put out has a certain major quality and integrity…I don’t have any regrets for any of that, other than some solos that I thought – oh I should have done this differently- but overall I’m pleased with my recording history. I feel this is my most ambitious album, maybe my best for several reasons. Number one practically I wrote or co-wrote all of the songs, nine out of eleven tunes. “Beggin’ For Change” I wrote that with Ronnie Brooks and with my wife Rosa we wrote “Toxic Love” and my former drummer Blaze Thomas wrote “Call Your Bluff”. The only cover we had is the Lou Rawls song “Dead End Street” which I rewrote the monologue to reflect my own biographical experience.

You have history with Rosa’s and Tony Mangiullo, so it makes sense that you are the first artist on the label.

Yes, right, we played the grand opening of Rosa’s Lounge forty two years ago, it’s hard to believe, forty two years that’s crazy! They started the label a few years ago but the pandemic slowed them down, we were presented with this opportunity given our history with Rosa’s Lounge and we did take the chance, it is a chance because it’s untried and untested but there are several aspects we’ve enjoyed. We got a strong voice in the decision making process, which is usually unheard of in a record label. And it’s not a twenty page contract, it’s pretty straightforward and we have a very small portion of the ownership of the label.

So how did you work on the recording? It was done both in Chicago and on the west coast?

Yes, in Chicago and Oakland. My producer, Larry Batiste who I met in Memphis at the BMA Awards of the Blues Foundation, he and I met and struck up a conversation, I told him I was in the process of producing a new record, we talked and it turned out we were a perfect match. We thought along the same lines. He comes from an R&B/soul/ funk background he was originally a horn player and he comes from the Seventies or Eighties era, like the Gap Band…and he’s a great vocalist as well. He did all the arrangements with the horns and the vocals and participated as a background singer. My musical tastes are unlimited, good music is good music, opera, classical, country, hip-hop, folk or jazz…as a youngster I absorbed the music of the radio airwaves which as a teenager at that time was Motown, The Beatles, Stones, Hendrix, Beach Boys, Peter Paul & Mary…you heard everything on the radio back then. I had no barriers in terms of what I wanted to express. So in this album you can hear different elements, jazzy riffs, R&B and the song “How You Living?” could maybe be described as hip-hop blues while “Ballad Of A Million Men” has reggae. So all these musical settings I feel comfortable with and I’m able to execute them on the harmonica because of my foundation that I learned from my mentors and teachers primarily Big Walter Horton, James Cotton, Carey Bell and Junior Wells. And also by listening I absorbed the styles of Little Walter, Sonny Boy and others.

With Cotton, Carey Bell and Junior Wells you recorded “Harp Attack” on Alligator in 1990.

Yes, time flies! And sadly they are all gone now.

Another one of your mentors was noted poet and writer Sterling Plumpp, has he influenced your songwriting in any way?

Oh that’s more the other way around. You know I was a student in his class at University Of Illinois. Sterling is from Mississippi, he had an uncle that owned a blues club in Chicago that Howlin’ Wolf used to play at, I don’t know the name of it. The way Sterling and I struck up a friendship is we had an assignment to relate a short story called A Summer Tragedy by the writer Arna Bontemps and one of the essay assignment was to relate the story to the blues. So I ran with that. And by the next class session he was reading part of my paper to the class and he said this brother Billy Branch really knows the blues. I held up my hand and said – excuse me sir, I play the blues. – And he looked at me in complete disbelief! He’s from Mississippi and he came up on blues and jazz. When he tells this story he says I looked like a young Barack Obama and so he says, there’s no way a kid like this could play blues, at just eighteen or nineteen years old. He said -what do you play? – I play harmonica. Would you bring your harmonica to class? So I did and I played it for the class. He was just astounded. And that’s how our friendship began. When the Sons Of Blues were working seven nights a week in Chicago you would see Sterling with a pen and paper, taking notes…I would give him advice to write a standard blues song, the AAB thing. It was a mutual collaborative relationship we had and to this day Sterling still remains one of my closest and dearest friends. He’s eightyfive and I gotta go visit him again soon, I last saw him about a month or so ago.

You wrote “Sons of Blues” together.

Yes and I recorded it two times, the first on the “Where’s My Money?” album and then on “Blues Shock” where we had the horns and we made it a little bit more funky.

Back to this record the song “Begging For A Change” speaks for itself, you are joined by Ronnie Brooks and Shemekia Copeland.

Well, it’s a social commentary song, I had a sketch version of it for about four or five years and then Ronnie and I are tight, he is like my little brother so I brought him in and we got to work on it. Ronnie came up with a really cool arrangement and then added some verses. So we shared the writing on that. Shemekia and I had been talking about doing something together, I asked would she come in on this and she graciously accepted. And I think it worked out beautifully. Shemekia has put out some social commentary songs on her records as well, her manager John Hahn writes a lot of her material.

And a few years ago you did the “Ballad Of George Floyd” with Dave Specter.

Right, you know this is an issue with people of color in this country and around the world, on a daily basis. You would think in 2025 everybody would accept everybody for who they are but unfortunately the momentum has shifted in the opposite direction. “Beggin’ For Change” we feel has the potential to be a global anthem, because of course you can see some of the disaster things that are transpiring here in the US, but it’s not just the US, I know even in Italy you all are facing similar challenges. On this album there’s actually four social commentary songs and also the title cut, “Blues Is My Biography” has some of that.

You got Bobby Rush on “Hole In Your Soul”, one of the elders left from that generation.

Yes, Buddy Guy, Bobby and Bob Stroger…I’ve had a good relationship over the years, he remembers when I first came on the scene. I asked him if he’d be kind enough to grace my album with his wonderful talent and without hesitation he said-sure, just let me know when and where I got to be. He didn’t ask how much it paid, he basically did me a favor like all of them did. And he did a great job, I was very pleased, it’hilarious when he says at the intro, the blues is the mother of american music and if you don’t like the blues you probably don’t love you mama. That’s classic Bobby Rush!

A few weeks ago, during an interview Jimmy Burns told me how seeing you and Lurrie play live in the late Seventies inspired him to play blues.

Oh you know that’s very unusual and Jimmy has related that story many times over the years. And I’m still engaged in Blues In The School, as a matter of fact I have a residency right now, so it is usually the older teaching the younger. In this case it was the first time the Sons Of Blues got paid for the 1977 Berlin Jazz Festival, which for everybody who’s interested, they can see that performance on Youtube. We debuted “Tear Down The Berlin Wall” which is on Alligator’s “Living Chicago Blues Volume 3”, that got me my first Grammy Nomination. But before going to Berlin we rehearse by sitting in in the clubs, like Theresa’s or Checkerboard. And Jimmy had a career in R&B, of course he knew the blues, he came up from Mississippi and his brother was Eddie Burns, who lived in Detroit and played with John Lee Hooker and many others…but when he saw us play it blew him away. And I didn’t know it for many years. When he first told me I was completely unaware of that. He said, Billy you’re responsible for me getting back into the blues. – And I was, what? What are you talking about?

Your longtime drummer Moses Rutues Jr passed away recently and last year Carl Weathersby passed too.

Well, Moses was my drummer for 35 years, that’s a long time. He passed just a few weeks ago and he was one of those guys that everybody loved. He was always upbeat, always the first one at the gig, he would set up his drums meticulously, he would polish the cymbals…he was the type of guy that would do anything for the band, if a guy didn’t have a ride or somebody’s car broke down, even if it was way across town he would say – I’ll get him. He was for all the band. He was really dedicated to me and it was a very tragic loss, he was doing pretty good but he had a fall and broke his hip, while the surgery was successful he went into cardiac arrest and never came out of it. He stopped playing for me but we stayed in touch, a dear friend, we truly miss him. Even Nick Charles, my bass player for over twenty years passed and Carl Weathersby, who was with me for seventeen years. And J.W. Williams who was there when we had the Sons Of Blues Chi-town Hustlers has passed. A lot of other friends like Don and Ralph Kinsey, Jimmy and Syl Johnson and a whole lot more…it makes you realize how precious life is.

Do you feel a kind of responsibility to keep it going for all the departed friends too?

Well, it’s been pointed out to me by several of my musical colleagues, people say things like -Billy, you’re one of the few guys who can play the Chicago style harmonica…and I realize that’s true, even if I did a lot of cross-genre collaborations and this album maybe it’s not a traditional blues album but it’s very bluesy. But I’ve played with african artists, Samba Toure and Sidi Touré or mexican artists like Son De Madera, an indian artist Sarah I can’t pronounce her last name though…and I enjoy it, because it keeps it challenging. But the Chicago blues harmonica, a legacy that I have been blessed to have been a part of, it’s almost a dying art…I mean there’s a lot of people who try to play it but I was blessed to learn from those masters. I missed Little Walter and Sonny Boy but I studied their records, but Sonny Boy taught Junior Wells and James Cotton and I learned from them and of course I spent a good deal of time with Walter Horton. And many others harmonica players like Good Rockin’ Charles, Easy Baby, John Wrencher, Big Leon Brooks, Jewtown Burks…those were all my friends.

And probably not that many people today remember some of them, or a guy like Wrencher, who used to play a lot on Maxwell Street.

I would go to see him, I used to hang out in Maxwell Street and then we played at the same Elsewhere on Sunday he had a matinée show and I was with Jimmy Walker and another dear departed friend, Pete Crawford. And John Wrencher, I’ll never forget, told me, – Hey Billy, I’m going down to Mississippi to see my kin folks, why don’t you come with me? We’ll drink some moonshine and chase some women…- I didn’t go with him, I don’t remember the reason, but he went down there and he died in his sleep and never came back. I feel blessed to have known many of them, great artists who never made any substantial money, never even acquired a big name, but they were genuine and talented musician in their own right. I’ve reached an age where I outlived many of my mentors, teachers or colleagues…having that personal connection was special.

It was different back then.

I came on the Chicago blues scene when it was still very strong. On the south side and west side, the black neighborhood, on any given night you could hear eight or nine different places that had live blues. You had guys like Lefty Dizz, Buddy Scott…Dizz was the link between my generation and his, he was the cool cat and he would always welcome the young guys. He was my first friend on the blues scene and he was a character. Like one of my blues sisters, Deitra Farr, says, you know what’s missing from the blues these days? Those characters! Their personalities where bigger…Junior Wells, Magic Slim, Hip Linkchain, James Cotton, Big Walter, Carey Bell, Jimmy Dawkins, they were all characters, bigger than life. Then you got guys like Fenton Robinson who used to come and sit in with us, Son Seals…and you could see them every week, most of them for free, a magical time.

And 50 years ago, around 1975, you joined Willie Dixon’s band.

Man, when you say it like that it really feels old! But you’re right, I’m one of the old people now. It’s deep, it’s like time went by in the blink of an eye. I haven’t really thought about that.

It was in those times that your recorded for George Paulus on his Barrelhouse Records, “Bring Me Another Half Pint”, what do you remember about it?

That was definitely the first recording that I sing on and at that time I was scared to death to sing but they insisted. I did “Hoochie Coochie Man” and I don’t consider that one of my best vocal moments, but hey I was young and I was just getting started. I didn’t know Paulus very well, all I know is we didn’t receive one penny for that recording, but when you’re young you just want to play, you don’t think about the money so much. It was an opportunity to get on a record is exciting for a young musician. I think it was recorded in Willie Dixon studio in the South Side like another recording I’ve done with McKinley Mitchell that was called “That Last Home Run”. I have to double check which one was first. The song was about Hank Aaron, the baseball player, breaking Babe Ruth’s home run record. It’s got the sound of people cheering in a baseball stadium. Willie was always two steps ahead, so he said, well Hank Aaron is about to break Babe Ruth’s record so I better write a song about that.

In the Eighties you recorded for L+R.

We did a Live album and a studio album, Young Blues Generation, which I think was a great example of classic blues you can hear, it was just magic, with Lurrie, I had just acquired J.W. Williams and Moses Rutues and we had Eli Murray on rhythm guitar. I think we may have recorded the entire album in four or five hours. This is where you can hear Lurrie Bell at the height of his skills, you can hear the genius in his play and as a result he forced me to play some very interesting things.

What do you think about this upcoming generations of blues artists, like Kingfish, Jontavious Willis, DK Harrell, Harrell Davenport or Sean McDonald to name just a few of them?

I think it’s wonderful to see the influx of these young highly talented male and female african american artists. Harrell Davenport at 18 years old sings like a 60 years old bluesman, he’s becoming very proficient on harmonica and guitar, when he comes to Chicago he stays with us, at my home, we spend a lot of times together. He studies, he’s very diligent, he’s telling me about recordings that I’ve done that I didn’t know. This year he and I were on the back porch barbecuing we watched the Chicago Blues Festival on my phone through a bluetooth speaker and I’m watching D.K. Harrell and Stephen Hull and I said to Harrell: do you know how long I’ve been waiting for you guys to show up? Even though I was not directly involved in teaching them I feel like I have a small part in that because I’ve been teaching blues since 1978, almost fifty years…

You were planting seeds in a way.

Exactly! After all these years it’s very important. When I teach blues in schools, right now I have a residency that goes eight weeks, these kids are not so much musically inclined, some of them are, but some of them the challenge is focus, they just can’t stay focus. But one thing I stress is the importance of the blues as african-american culture and culture in general because the blues has affected music all around the world. It’s fair to say that Chicago blues had a big part in the British invasion, they all cut their teeth listening to Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter…so for these african-american musicians to realize that this is part of their culture is important, because our culture here as african-americans was virtually erased. And now there is a current movement to push back against any inclusion of african-american culture in some schools and some states it’s forbidden to teach it, in some place there is a movement that says that slavery was a good thing, that they brought africans over here to learn skills and they had free food. And you know that is complete bs. And I learned this from Willie Dixon, every day that we have blues in the schools I invite four or five kids to repeat a call and response slogan, why are we here? To sing and play the blues! And what are the blues? The facts of life. What makes the blues so important? They are our history, our culture and the roots of american music. It’s a different age, we’re in a technological age, phones, computers are the dominant influences, the challenges of teaching are affected by it.

You should write a book someday.

Oh everybody keeps telling me that, my wife Rosa, everyone… maybe I will. We have high expectations for this record, it’s timely and there’s a lot of message in it, a lot of thought.

Comments are closed